A hand is not simply part of the body, but the expression and continuation of a thought which must be captured and conveyed. (Honore Balzac, Le Chef d’oeuvre inconnu, in Merleau-Ponty, 1964: 18)

Thinking Hands – Putting making and materiality at the core of Design Education

Partners:

CCW Foundation

3D/ Spatial Foundation Students

Paul Lindey

Digital workshop Technicians:

James Hopkins

Priscilla Pang

Ameet Hindocha

ARP The Intervention- Workshop Structure:

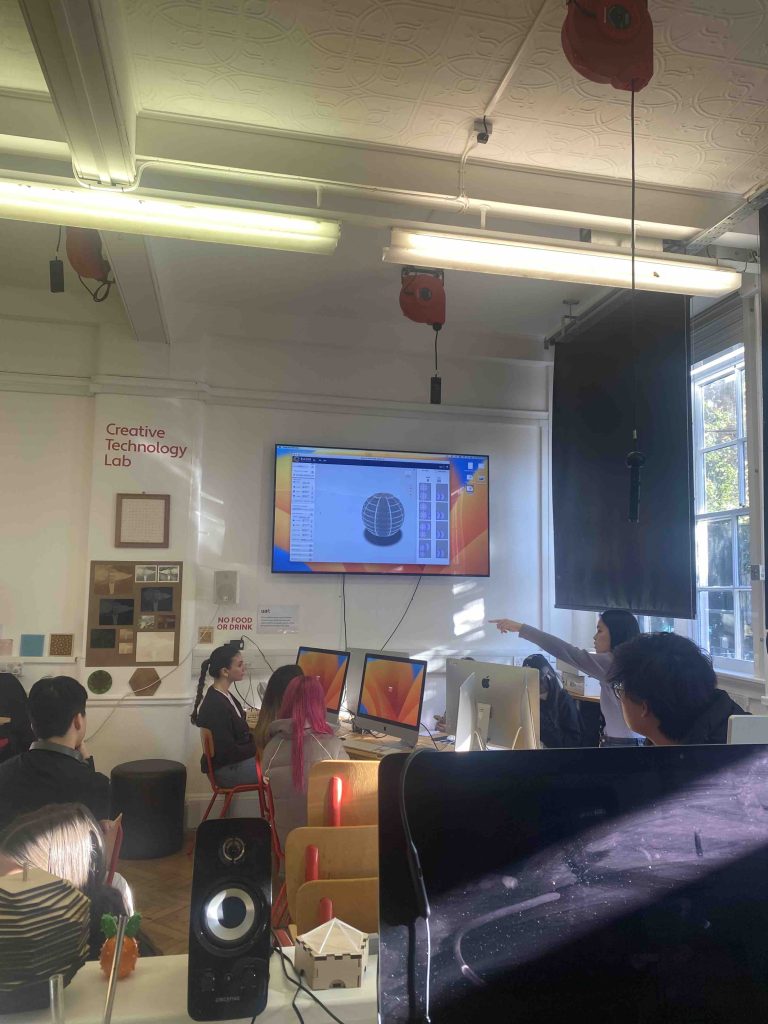

4 X 3 hrs workshops split between the digital workshop and G2 Design Studio

15 students per workshop

The structure of the workshops is split into two parts:

45 mins in the Digital workshop

Presentation of the workshop structure

Introduction of James and Priscilla and their role in the Foundation

Presentation of their background and current practice

General discussion of how to book the workshop, opening hours and a consultation session with one of the technicians, the different tools and processes available

Presentation of the material library available in the digital studio and the different processes

Discussion of the importance of experimenting and testing material and process in Design

Technicians lead the session showing a demonstration of the Slicer tool software, Blender and the mesh plugins, the Makercase software and the open-source online library

Q&A

Students are given a sphere sliced with the slicer tool and shown how to assemble it

Students are given a diamond-shaped foldable piece of paper and shown how to build it via the mesh tool on a blinder and construct it by hand

The session continued in the G2 studio led by myself

Presentation of the next stage and different materials available

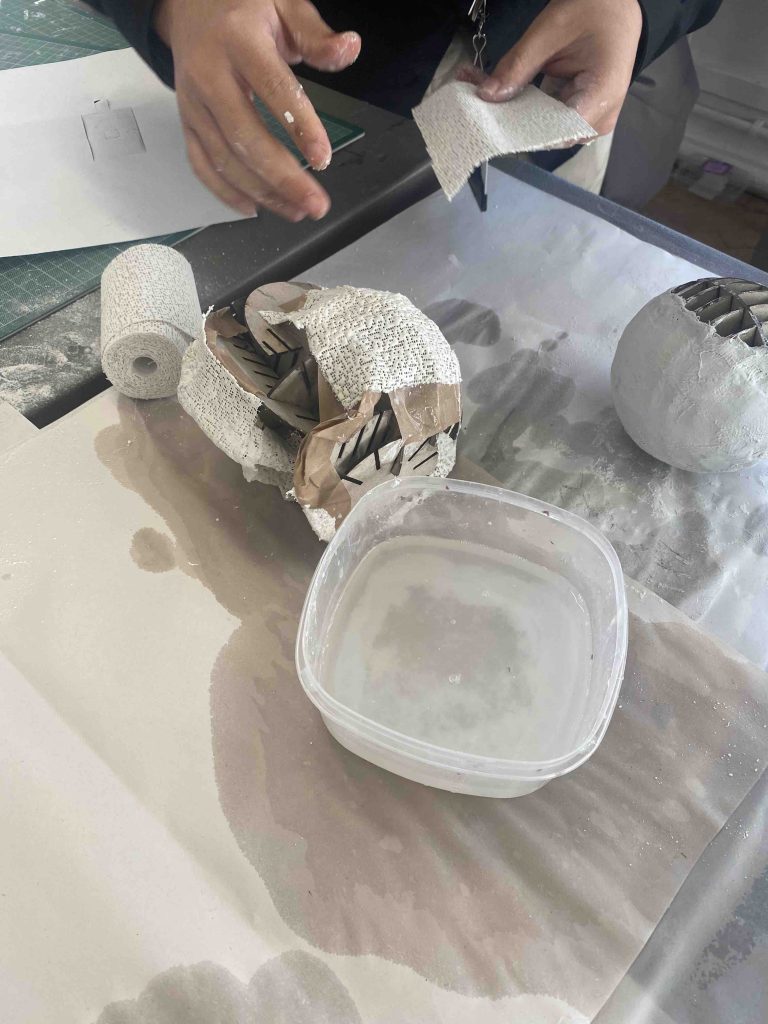

Modroc

Papier mache

PVA glue

Acrylic

Card

Explanation of the two material properties, their application, its history

Demonstration of making a card model, cutting and scoring

Demonstration on how to make papier mache – its advantages cost-wise, sustainability, recyclability, lightness and resistance and how it can be combined to a digital paper model using a slicer tool, maker case or blinder

Students have a 1H15 to test and experiment with the process and to produce an experimental model

In the last 15-minutes, some feedback form was distributed and completed

Last thoughts and comments

End of the session.

The result was added to a shelf and exhibited in the studio G2 until the end of the term

The problem:

The the importance of embodied cognition, making and materiality remains under-stressed in Design education which puts an emphasis on cognition in the form of ‘thinking’. This creates a lack of materiality and making culture in UAL, in students projects which are missing crucial development, a degreasing making confidence for students and stress on the students/technicians – tutors/technicians relationships, and missing opportunities to address materiality, sustainability and critical making.

The Questions :

How could we encourage students to learn how to make things and think with their hands? How could it be integrated into design education?

How can making and materiality be no longer reserved for the workshop space but be included as physical space in design studios?

How could encourage students to test their ideas and concepts through making before their workshop booking? Could this embodied experience ease their relationship with the technicians and challenge the “service provider” aspect of the workshops?

How to leave enough space for self-reflection and self-initiative in education?

Rational:

This ARP project is looking into the space left to make and materiality for the 3D and Spatial design students in the Foundation.

We are learning from both our heads and also our hands, yet in current UK FE and HE education, hands-on learning is still associated with a soft skill, linked to the world of craft, DIY or Apprenticeship career and not as an essential skill for future design lead professional practice.

It examines the relationship between a curriculum angled to “learn how to be creative” and relies heavily on idea and concept generation and CAD generation and less and less on investigating the world through making and materiality.

For students who grow up during the COVID pandemic and through the digitalisation of the design practice, how could we encourage students to learn how to make things and think by their hands? How could it be integrated into design education?

Theory:

Creation does not rely only on the cognitive and rational but also on physical and material dimensions (Pallasmaa, J. (2009) The Thinking Hands Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture, Wiley.)

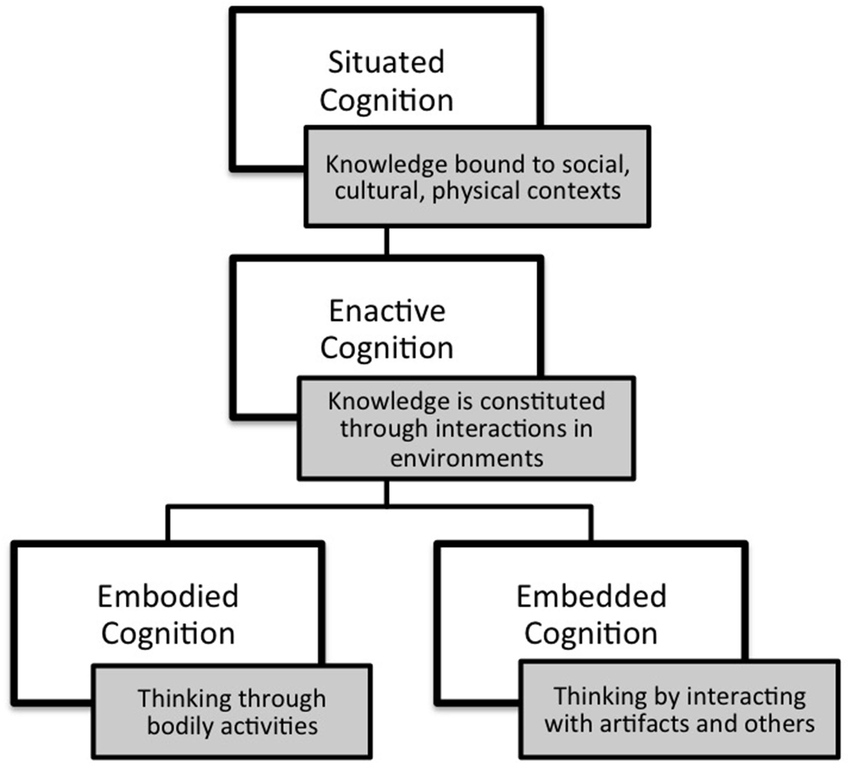

Thinking definition has to be expanded to also the body and the cognition 4E (Newen, De Bruin et Gallagher, 2018)

The “4E” approach to cognition argues that cognition does not occur solely in the head, but is also embodied, embedded, enacted, or extended by way of extra-cranial processes and structures.

Manipulating materials and testing processes create new knowledge and skills while activating innovation and self-reflection.

This project is also looking at the UAL social justice agenda and its sustainable engagement and how to design a better world through educating future practitioners.

The philosopher Maurice Merleau Ponty talks about how knowledge is deep into our body and how the perception of the world around us comes from our physical interactions as embodied experiences.

Bruno Latour and Richard Sennett highlight the role of understanding material and fabrication processes in our cognitive experience. There is a direct link between society, social system and social justice with our knowledge of materiality and processes.

Following the UAL grading system and learning outcomes, we can see here again that Design learning is not a direct line from the concept to the realisation but is from the confrontation between the material, processes and reflective practice to an outcome which integrates all these aspects.

Making is being in the action, reflecting with a teaching staff while making is important to link the hands to the head and the crucial step is to reflect post-making, to solidify the learning and going back on the experience to make memories.

The Goals:

Structure the making learning to the task, the material, the environment and the fabrication processes.

Together they form a network of learning which are all interdependent.

Results and conclusion- What did I learn? What is next? :

- It was important to collaborate with Technicians on structuring the workshop, planning the logistics and giving them enough notice to schedule it in their daily tasks, student consultation meetings, and staff meetings and making sure there were no clashes with other workshop activities.

- It was important to guide the students to the workshop and define the workshops as a place of learning and not only of execution or as a service provider.

- To re-explain the booking slots system but also what was expected from the students, bring a sketch, dimension, inspiration and book a consultation with the technicians.

- It was crucial to show the different materials, fabrication processes and material/processes library around the workshop to students to be aware, spike imagination and questions. To mention that they can be a conversation starter to discuss a concept or idea.

- It was important to highlight the role of the technicians as equal to the academics, and creative practitioners and create an emphasis on how all teaching staff are connected, experts in their practice but also interdependent to create a rich curriculum.

- It was important to deliver the first part of the session together (Academics and Technicians) but also to leave space for the technicians to lead their part through their expertise – to enhance fluidity in teaching but also in between these teaching spaces, and open the circulation of movement between the studios and the workshops which are on the same floor.

- It was important to show and explain the different fabrication processes associated with samples, and models to spike questions and comments.

- It was important to leave freedom to students to take the initiative and learn, experiment and hack the making process to not just make it as a copy exercise.

- To encourage students to look around them, push them to ask questions to others about their process and to reflect while making.

- Making enable more equal relationships between tutors and students, break some of the cultural barriers but also language difficulties of the international students who are using their hands but also learning new professional vocabulary.

A structured workshop was essential to put the students in a condition of learning and feel confident, curious and trustworthy, not enough structure would have led to a too-superficial experiment.

However, experimenting with a progression of structure from teaching to slowly letting students take over and make from their initiative was beneficial for students to reflect on how they could use this technique for their ongoing project.

As an educator or technician you can impose materials and a fabrication process, however leaving enough time and space for the students to take over is essential.

It depends of course on the teacher and the student’s personality which can be more or less attracted by the materiality or making process. However, it is important to teach all students how to make and deal with materiality from an embodied workshop or experience to break boundaries between the heads and the hands but also to fight the crystallisation of roles in the university and the hierarchy of skills.

In summary

- We can say that the interaction with materiality is a structural aspect of the process of design learning.

- I am aiming to continue investigating how the embodied experience can be equally central to the curriculum.

- Physically as creating a bridge between Academics and Technicians, inviting them to take part in tutorials and bring their expertise,

- By leading more workshops in the workshop facilities,

- By inviting technicians to come to share their practices and expertise,

- By sending discussing briefs with them and having their input on the learning outcomes,

- By asking students to produce process books as part of their brief response

- By creating a student-led material library in which students every year would display material samples or process their work for their FMP project.

- This material library would be photographed and archived and would be the starting point of the first UNIT 2 1st project called Manifesto. The material library would be dismantled, stored archived and updated with new material samples and processes.

Hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom . London: Routledge.

Friere, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the oppressed . London: Continuum.

Pallasmaa, J. (2009) The Thinking hands Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture, Wiley.

Pallasma, J (2017) Embodied and Existential Wisdom in Architecture: The Thinking Hand, Vol. 23(1) 96–111 Body & Society, Sage.

Newen, A, De Bruin; L et Gallagher, S. (2018) Thinking avant la lettre: A review of 4E Cognition. PMC – NCBI

Wesseling, J and Cramer, F. (2022) Making Matters, A vocabulary for Collective Arts, Valiz.

Ratto, M. (2011) Critical making: Conceptual and Material studies in technology and social life. The Information Society27, no.4 pp 252-60

Hertz, G. (2012) Critical Making, Telharmomium

Olunkwa, E. (2023) Martino Gamper and Max Lamb Pin up 34.

Available online

https://www.pinupmagazine.org/articles/martino-gamper-and-max-lamb-interview

Roux, C. (September 29 2023) Designer Max Lamb: “Touch, touch, touch”, Financial Times.

available online

https://www.ft.com/content/616b92de-6f14-4d72-8714-65b0b95f1f4d

Latour, B. (2007). Reassembling the social: An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford

University Press